Whose fault is it?

Why are GB electricity prices currently so high compared to other countries?

A few months ago, I approvingly Re-X’d a blog post by Michael Liebreich (Thoughts of Chairman Michael and an excellent podcast). I got this response from Peter Atherton.

Guy - you and Michael have done much to formulate UK energy policy over the past 15 years. But your policies have delivered; 1. some of the highest energy prices in the world; 2. de-industrialisation; 3. poverty; 4. no measurable reduction in world temperatures or the rate of temperature growth. Perhaps some humility would be in order. Those who question this are not naive or stupid or indeed 'nostalgic'. Perhaps they are just looking at what these policies have delivered and wondering - if this equals winning, what the hell would loosing look like?

For those of you who don’t know Peter, he was one of the City’s leading energy analysts for many years. He wrote an excoriating front page for the Spectator on why the the nuclear power station at Hinkley was a bad idea. And he was a great informal sounding-board for me while I worked in Government.

While it is flattering for him to assign me influence over UK energy policy over the past 20 years based on the three years I was ‘inside’ with no actual decision-making power (plus some think-tanking before and Catapulting after), his message niggled. Either way, it was a fair challenge. Electricity prices are too high. As I said in my ‘Everything is Changing’ opening Substack, this is a real problem both for the politics of climate action, but more importantly for manufacturing businesses and the millions of people who are struggling to pay their energy bills at the moment.

So before we get to what to do about it, any good strategy starts with diagnosis. So whose fault is it that UK electricity prices are so high?

Name and shame blame game

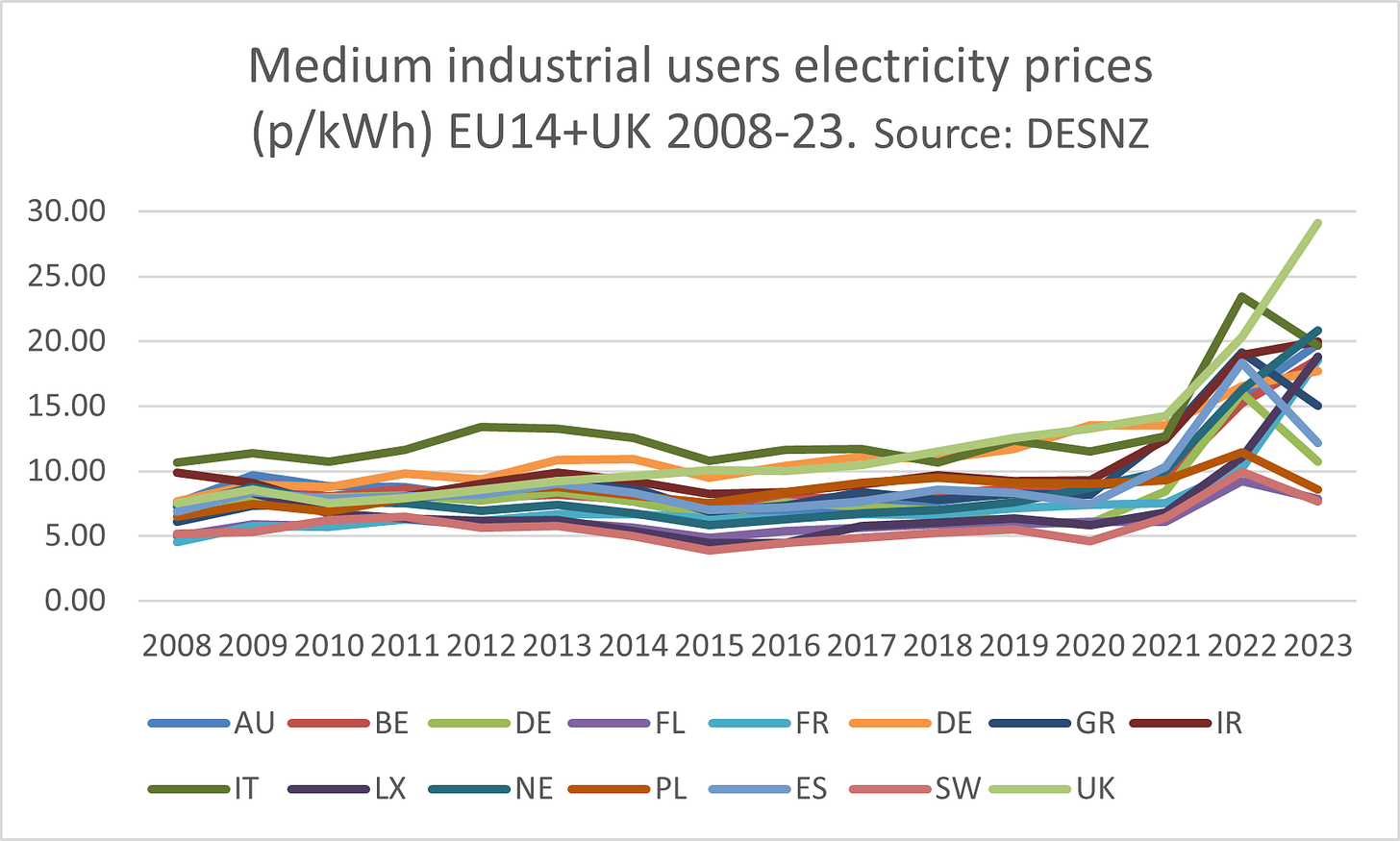

This chart, created from DESNZ/Eurostat data, shows that the UK (we actually mean GB here, as Northern Ireland is part of the Irish electricity system) has moved from middle of the pack to the most expensive for industrial users vs other rival European countries. And it is our competitiveness that matters for industrial and commercial businesses (of course, these prices are much higher still vs the US or other OECD countries, which are are effective global competitors). We see a similar pattern for domestic users and large industrial users. Not good.

So what is driving these increases? Once we work that out, we can start dishing out detentions.

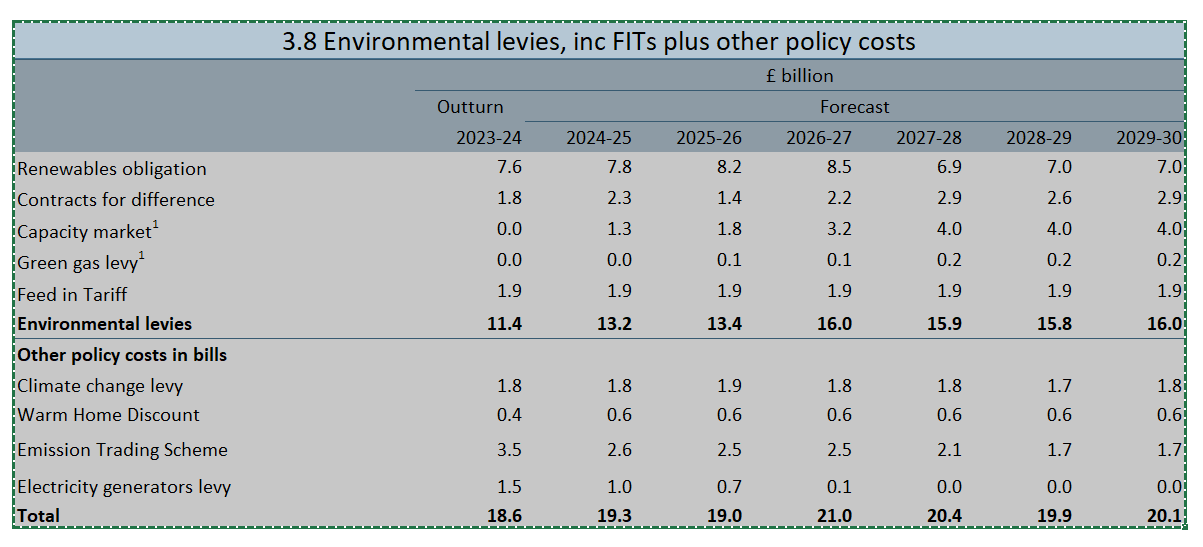

Defendant number one: ‘Those bloody windmills’? Well, the overall cost of supporting renewables (offshore and onshore wind, solar, biomass, plus some other minor technologies) has certainly increased significantly since 2010 (see chart below). The cost of renewable technologies has fallen significantly over that period (although it is likely jumping up a bit as interest rates have risen, among other factors), but we are still paying the price for some very expensive early renewables, particularly the feed-in-tariff scheme for small scale solar and early offshore wind. Finding out how much this all costs is tricky (at least I found it tricky). I have tried to bring it all together in this table (which is my table adapted from Office for Budget Responsibility data. You can find the original here)*.

Personally, I would not count the capacity market as environmental levy (or things like Warm Home Discount, which help the fuel poor), but I am not the OBR. That said, it was introduced at the same time as Electricity Market Reform to give greater confidence on security of supply as intermittent renewables were being rolled out (for what it’s worth, I argued against the capacity market from outside Government before it was introduced - I am a bit Texan like that). Renewable support costs were pretty negligible in 2010, so this is certainly a key factor.

On climate taxes (Defendant number two), post-Brexit the UK has its own Emissions Trading Scheme, which is generally a bit lower in price than the European one. However, we do have our own Climate Change Levy (paid for by business and industry, with some exemptions) and Carbon Price Support (which does not appear in the OBR tables), which will push up vs European competitors.

Why did the UK go so fast on renewables? Some people blame the introduction of the Climate Change Act (CCA - the UK’s carbon budgeting system) here, which was a cross-Party endeavour although proposed by the then-Labour Government. It is worth remembering that until relatively recently the CCA did not include the power sector (the odd traded/non-traded split). My experience was that the key driver of the rapid renewable ramp-up was the EU’s Renewable Energy Directive - part of the 2020/20/20 package. It was certainly the thing that Treasury officials were more concerned about breaching than any domestic commitment. So who signed up the UK to particularly tough renewables targets? The rumour, although never confirmed, is that then-PM Tony Blair got confused between energy and electricity in the negotiations and agreed to 20% of energy coming from renewables rather than 20% of electricity. An expensive mistake - as 20% energy translated into c.35% of electricity, from basically a standing start and no major hydro or biomass resources, which helped other countries. Because we are swotty, the UK basically met this target even though, because of Brexit, we did not, in the end, need to. We also decided to pay for what was essentially an innovation support policy through people and businesses’ energy bills rather than general taxation, which would have been more progressive (but would require other taxes).

Are the UK’s renewable subsidies much higher than other countries, even after that splurge on renewables, some of which were very expensive? I have struggled to find decent data on this, but from what I could find see the UK is not spending significantly more on renewables than other European countries, but is probably higher than other non-EU developed countries. [If you have any better data sources, leave a comment.] For heavy industrial users, the introduction of the ‘Supercharger’ protection by the last Government certainly meant they are no longer disadvantaged vs Europe on a policy costs basis. This is of little comfort to heavy energy users outside the ‘energy intensives’ category (lots of manufacturing and, increasingly, data centres).

To the Peter challenge on whether I and Michael are to blame on this? I cannot speak for Michael, but I spent 2010-2014 outside Government making a living arguing against the RE Directive, and in particular high subsidies for offshore wind and small-scale solar. When I was a Government adviser, ministers spent the first few weeks butchering subsidies for solar and biomass (and banning onshore wind in England, which was rather silly), as they felt they had got out of control and there was a risk of a consumer backlash. I was heavily involved in pushing for greater competition in CfD auctions and for a price cap on the auction for the one renewable technology we did decide to support in 2015 - offshore wind. This competitive pressure helped bring prices down, I think. I was also an opponent of the tidal lagoon scheme in Swansea, which I though was very bad value for money (although from memory, Peter Atherton was supportive).

There are other costs associated with renewables, of course, as they make balancing the grid vs dispatchable power stations. These size of these costs are disputed, and will change on wider factors in the system (which is why I strongly favour a balanced technology approach). A blog post for another day, perhaps, as it is a huge subject by itself. And lots of other markets have also rolled out solar and wind at a fast pace.

So if renewable support, while a significant and growing part of the bills, is not out of hugely synch with other European markets (although will be globally), what is driving the UK’s comparative disadvantage in electricity prices?

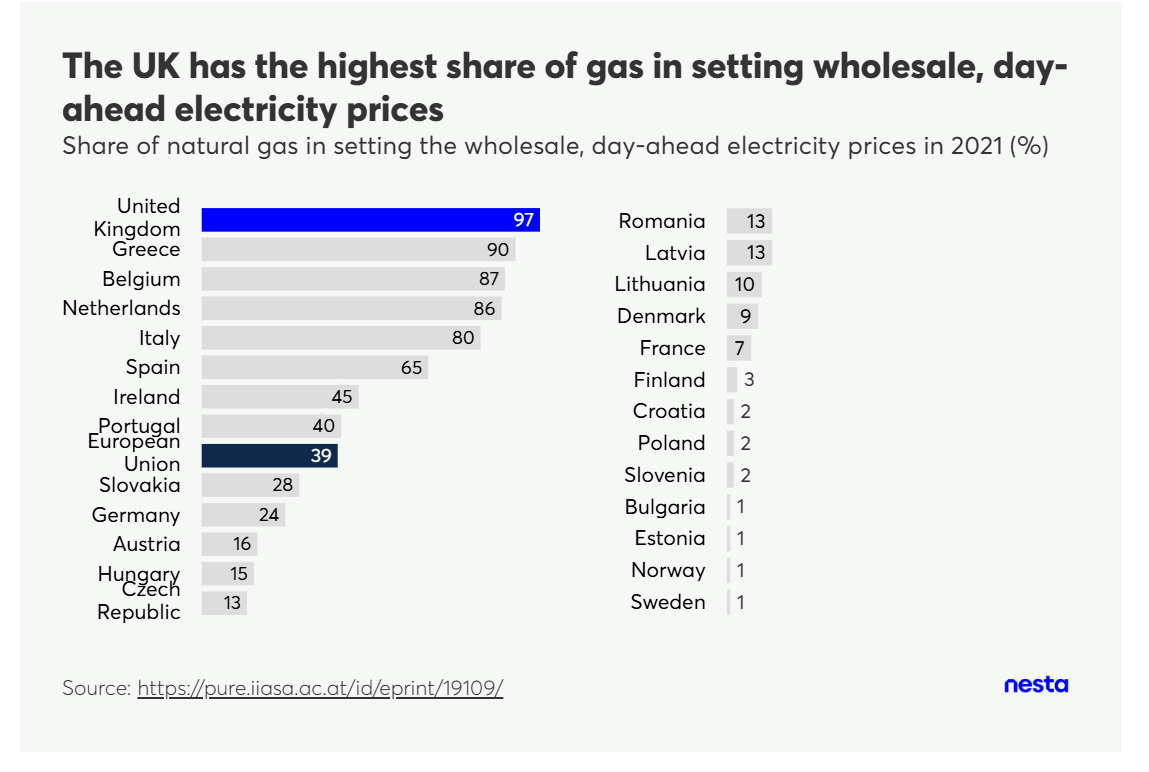

Defendant number three: gas. The UK power system is currently very gassy. Gas sets the price in the wholesale market a lot - c.97% of the time - which is much higher than other rival countries. See this nice Nesta analysis below. And obviously international gas prices have risen a lot in recent years (I think we can mainly blame that one on Mr V Putin).

In an ideal world, you would have a better balance of technologies to provide a hedge against price spikes in one particular sector. So why is the UK so gassy? There are two main reasons. First, a total and negligent failure to build new nuclear since the 1990s, when we opened Sizewell B (Defendant number four). I was not in Government at the time they decided to not support nuclear in the 2003 Energy White Paper (this was reversed in 2006, but killed much momentum), but understand then-Environment Secretary Margaret Beckett was vehemently opposed. The main blocker, or at least decelerator, over the past 20 years to new nuclear was, in my experience, the Treasury, who bought the strategic case that it was needed, but just never liked any of the deals that actually turned up. We have also failed to focus hard on reducing costs (one where I tried but failed - and delighted to see the new Government looking to make progress on this, thanks to the pressure of Britain Remade, Looking for Growth, DayOne and others) and deciding what the right financing model was, ie how much state involvement you should have. The latter was complicated by the 2010 Coalition agreement, which said there would be no subsidy for nuclear (so blame Oliver Letwin, who drafted the agreement, and Nick Clegg, the Lib Dem leader?). If it was me, I would have heavy state involvement in building a fleet of the things, and then sell them.

Beyond the failure to build nuclear, we have also closed our coal-fired power stations (Defendant number five: no coal), with the decision announced in 2015 (in a speech I wrote a lot of, so certainly take some of that blame). This has not happened in Germany and other markets, so the filthy stuff sets the marginal price more often. Of course, if you think closing coal was a bad idea probably means you are more relaxed about risks around toxic air and climate. This is certainly a factor in the short term, but is unlikely to be reversed.

So how do we reduce the reliance on gas as the marginal plant and/or get the cost of gas down? Some argue that one of the things we could do to bring down gas prices generally in the UK would be to open up more North Sea licences and/or explore for shale gas, to replace our dwindling North Sea resources from conventional gas. The North Sea is a dwindling basin. I was supportive of shale, but the politics were horrible, just ask the MPs who attended the public meetings near the site of Cuadrilla’s proposed well. I think lots of that opposition was built on nonsense science, and is part of the wider malaise of the UK to just get on and build stuff, but it was an argument that was lost. If we are going to use lots of gas as we transition (and even beyond, if we are going to use CCS), I would rather it came from our own territory, where we could tax it and use that money usefully. It is not clear how much even a significant shale find would bring down our costs, as gas is internationally traded. Probably the key supply-side factors in short-term gas prices are Ukraine and how much the shale-rich US is willing to export to Europe, which are both, er, uncertain.

We have built a lot of renewables, which could bring down wholesale prices if they were setting the marginal price enough. They could even create negative pricing, where you would be paid to consume (this happened briefly last weekend when it was super sunny, BTW). But we are not yet realising the benefits often enough in low wholesale prices. Partly that is because of a failure to build enough network to connect the renewables in Scotland to places where there is demand. That follows a lack of strategic planning, which is now being improved through the introduction of various acronyms (SSEP, RESP, LAEP, RESPECT) We have also failed to design a more granular locational wholesale market that allows us to benefit from zero marginal cost renewables. I certainly wish I had done more on both in Government.

The gassiness of our wholesale electricity market is certainly a problem, I think the major reason for our worsening competitiveness in the short-run (I think this nice piece of analysis by UK Steel supports that). Will the drive to deploy more renewables and networks help reduce that dependence on gas? That is certainly the current Government’s bet with its Clean Power 2030 mission. It will certainly make it less likely that gas sets the marginal price (estimate vary significantly, between 15 and 50% of the time, although I would like to see more analysis of that). Going faster risks putting pressure on supply chains that could drive up costs, which will be locked in through the CFD for renewables. And, of course, going faster on renewables or nuclear is also a hedge against the staggering cost of the energy support policies introduced in 2022/23 in response to the Putin-induced gas price spikes. These cost the taxpayer c.£52bn, although was offset by some windfall taxes (which are captured in the table - it is not clear how they are feeding through to wholesale prices). Either way, right now we are in that awkward phase where we have grown our renewables a lot, but have not yet got a system that is taking advantage of them.

Once these costs were added, could we have divided up the pie so that different parts of the system pay different amount (Defendant number six: cost allocation)? Governments since privatisation made a choice to spread network, renewable and other policy costs evenly between industrial, commercial and domestic customers, although the measures in the ‘Supercharger’ reversed that for the most heavy industrial users from 2024. The argument was that there is no right answer on whether consumer or industrial energy consumption is better, and we should allow the market to reveal the right balance - this was something I argued for in Government, mainly to protect domestic consumers, also known as voters. On reflection, I tend to think Dieter Helm is right that such an approach was a mistake and we should have done more to protect industry earlier, as other countries did (Ramsey pricing choices).

That is my view of how we got to where we are now. There are a lot of complex and interconnected reasons for the position, but I think the evidence shows that the major short-term reason for our reduced competitiveness is the gasiness of our wholesale market. I think early renewables were expensive (and were innovation, so should not have been imposed on bills - a decision we could reverse) and the UK went faster than others between 2010 and 2020 driven by the Renewable Energy Directive, which has also contributed, certainly to our global position. I think our carbon taxes are slightly out of kilter with others, although the revenue is helpful and I would rather we taxed environmental ‘bads’, like carbon, than other things. I think our failure to build nuclear and focus on measures to reduce its cost is a collective scandal. And I think closing coal was the right call, all things considered, but if the plants had been kept open may have mitigated the short-term pain we are facing now around the margin.

As the unhelpful direction-giver to a tourist looking for directions says: ‘Well, I wouldn’t have started from here’ (even though I played a limited part in providing some directions that got us here). The question is what we do about it, which I will return to in future blogs….

*One side note - I spent a LOT of two Saturdays trying to identify and then piece together all this data. Thanks to help from Paul Homewood at the ‘Not a lot of People Know That’ blog, who kindly pointed me in the right direction (Paul’s blog certainly more sceptical than I on climate action, but he had done the hard work on the data which I appreciate). The Department of Energy and Climate Change used to publish this annually in a nice clear document, but that was stopped in c.2016 when there was a lot of worry about energy bills (I think I was in the room when it was decided not to publish it any more, although I was not pushing it and probably half-thought it was the wrong thing to do). Either way, in a delicious irony, the decision came back to bite me when I started writing this post…

Really thoughtful piece; greatly appreciate the insight from someone who’s seen this unfold up close. If gasiness is the answer, then I think some of the underlying premises need more scrutiny. Delivered gas prices aren’t fully global (domestic production and contracts matter), and volatility only really kicked in post-Ukraine. But UK electricity prices were already high well before that. so what was driving the gap?

Great, persuasive post.

The thing that I regret is that for so many years now we’ve heard ad nauseam what johnny-com-lately-Octopus thinks, wants to do, etc and very little from people like you and others who know what they are talking about.

I am sure that in energy circles people know of your work but it’s infuriating that in general discourse you only hear about Octopus