Everything is changing...

Messy geopolitics, economics and technology mean that many of the assumptions that have underpinned the climate and clean energy consensus are fracturing fast. What to do next?

The two most important charts in UK energy policy right now:

The cost of UK electricity vs international competitors (this is industrial electricity costs)

And if you the kind of person who prefers their charts without the back of

’s head, a similar message can be found in the below, although this is focused on domestic electricity prices (and yes, I know this makes a total of three charts):Either way, the message is the same: the UK’s (well GB’s, to be accurate) electricity system - gassy, renewable transition-y, nuclear declining-y - is very expensive per unit of electricity bought right now. This situation has got worse compared to 10/15 years ago, when we used to be safely mid-table or above vs European competitors (we still remain Champions League qualification level in gas prices). This matters for the economics - damaging our competitiveness in some sectors (manufacturing, heavy industry in particular) - but also the politics; ‘net zero is damaging growth, so we should stop’ (an critique of net zero was launched by the leader of the opposition this week, of course).

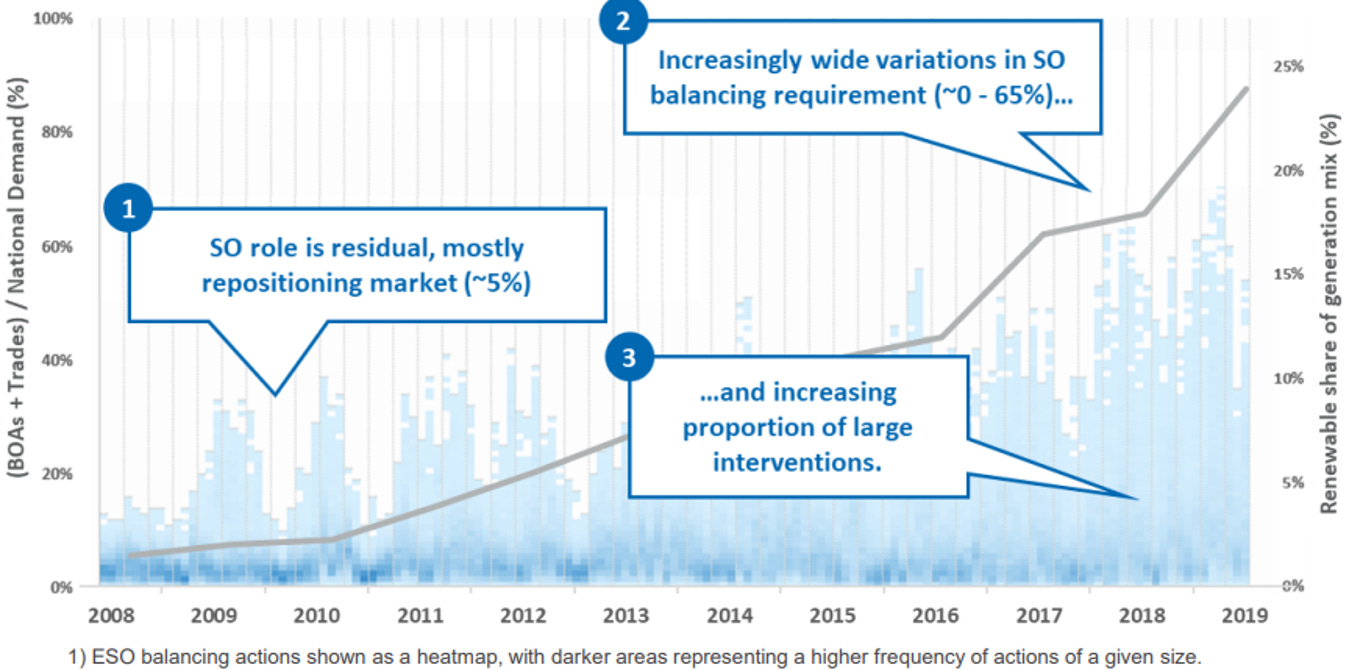

This slightly out of date chart, produced by the Electricity System Operator before it got famous and became the National Energy System Operator (NESO), shows how often the system operator has to take ‘balancing actions’, where they have to correct what the market has provided to ensure the lights don’t go off. They do this by switching on back-up plant that wasn’t expected to run, requesting changes in interconnector flows, that kind of thing. Every blue dot represents a half-hour period. The higher the blue dot is on the y-axis, the more balancing actions the system operator has had to take in that period. As you can see, the blue dots are getting higher and higher, and quite often the system operator is having to re-dispatch more than 50% of the market compared to 15 years ago, when it was only doing a bit of residual tinkering, as per the original design. This shows a system starting to creak.

What you think is causing what these two charts are showing (high electricity prices and a creaking electricity system) and what to do about it are the most important questions facing Britain’s electricity system. And they challenge Britain’s aim to be providing a compelling example of how to decarbonise your economy to the rest of the world. As electricity becomes a much more important part of the future energy economy (electrified heat, transport, industry, including data centres), addressing these tensions is essential.

And beyond those UK-centric charts, the wider sands are shifting. I have started this substack not JUST because all the cool kids are, but because I think the events of the past few weeks have shaken many of the assumptions underpinning climate and energy policy over the past 15 years. Or at least they have revealed some of the contradictions which have been simmering away for a while… And while there are significant risks in any change to the international and domestic architecture for those of us who are concerned about the climate, I also think this fragile context creates an opportunity for a re-winning of the arguments about why climate change is essential and urgent (and also how best to do it).

My central case a few months ago was that Trump would win the election, but that he would be a pretty ineffectual president, struggling to get significant stuff done, like his first term. That assumption was wrong. He has created a team that, whatever you think about them, is having profound impact. Most significantly, his undermining of NATO has meant that European countries have realised, perhaps far too belatedly, that the US defence shield cannot be relied upon in the same way.

That led to a slightly obscured but, in my view, very significant decision for the climate ambitious a few weeks ago when the UK said it was going to increase its defence spending and it would pay for that by cutting its overseas aid budget. It is not that well understood that a significant portion of overseas aid spending, both from the UK and internationally, goes towards climate-related action in developing countries (the argument being this helps countries reduce their emissions as they develop, which helps those countries in particular both in development and climate risk terms as they are the most likely to be damaged by the negative effects of climate change). This budget is a crucial part of the deal underpinning the international negotiations, which is basically: ‘We (developing countries) will all sign up to your targets, if you rich countries grease the wheels a bit.’ One very senior US diplomat once described this process as ‘dangling expensive bilateral goodies’ in a meeting I was in at the Paris negotiations. All par for the course in many international negotiations.

Now it looks like the UK, a leader in both climate action and climate diplomacy, is not going to be able to dangle as many goodies (which, let’s be honest, were nowhere near as impressive as America’s). And this US administration is not going to dangle any at all. How many other stalwarts of the international climate finance funding coalition - always a bit shaky, let’s be honest - will follow the UK’s switcheroo? And what does this mean for Brazil’s hosting of COP later this year?

At the same time, this combination of fragile geopolitics leading to greater demands on defence spending and anaemic growth mean the UK Government has a very tough spending review decision ahead in a few weeks, just as the bill for Carbon Budget 6 (and the newly proposed 7*) is due to be paid. The shopping list includes: new nuclear, including small modular reactors; carbon capture; hydrogen - for power generation, electrolysis, storage and industry; converting millions of homes and non-domestic buildings to low carbon heating; electric vehicles and charging points; and, in my view most importantly for the UK’s competitiveness and contribution to global climate efforts, innovation in new energy technologies. Now not all of this needs or indeed should come from public funding and much of it should pay off in the long term. Regulation and tax incentives could do lots of the heavy lifting (something I will blog - or is the verb to substack? - about later), but the politics of those alternatives are not easy.

So we could have a situation where, in a few weeks, we have a spending review which stretches the credibility of the UK’s ability to meet Carbon Budget 6. At that point, environmental lawyers will get twitchy about whether to launch court actions to challenge the UK’s plan, as they have done regularly over the past 10 years. Whether they do that, whether they win and what happens next is very uncertain….

That fractured geopolitical and economic context (I have not even talked about tariffs), plus the implication of the two charts set out above, have created a fragility for the climate consensus in the UK probably not seen since the growing awareness about climate change in the early 1990s. As a result, decisions over the next few weeks could have profound implications for our ability to manage the risks of a warmer planet.

Or, perhaps, none of this short term tumult really matters in the “long arc”, and the central challenge remains the same as it ever was; focusing on low carbon solutions which are better than the alternatives. Technology will save us…

This substack will explore those issues; in this messy context, how do we make the transition work: technically, technologically, politically and in terms of policy? It will look at some of the most exciting UK companies trying to capture the opportunity these challenges present. And I will also revive some older blogs from other platforms, where they are still relevant. Because, while everything is changing, plus c'est la même chose…

Do let me know what you think, and what I should be posting about.

***

*The UK has a system of five-yearly, legally-binding greenhouse gas emission targets which the Government commits to based on the advice of the independent Climate Change Committee.

Other stuff I have learned from recently on this topic:

- The Era of the Climate Hawk is Over

- Growing to Zero (which demolishes some of the nonsense some the recent from one finance sector analyst)

- Is Net Zero Good or Bad for Growth

Ben Shafran His latest 10 Things I like and don’t like (also includes critique of the same finance sector analyst).

- The Climate Change Act is Flawed

Danny Kennedy US’s Petrostate vs China’s Electrostate

Excellent first post Guy. Sets the scene well.

Hi Guy, these are some really pertinent reflections. On the geopolitical dimension, your piece touches on one of my core frustrations with the climate agenda over many years: it rests on myopic “end of history” assumptions forged in the lull between the fall of the Berlin Wall and the fall of the Twin Towers. I don’t understand why it’s taken Trump’s return to jolt parts of the climate movement and policymaking establishment into waking up. He’s not the cause — he’s just the accelerant. The international rules-based order was already eroding. America’s pivot to Asia began under Obama. Robert Kagan — who has advised both Republicans and Democrats, including John McCain, John Kerry, and Hillary Clinton — warned in 2008 about the “return of history” and the challenge of Russian and Chinese irredentism. Now it’s here, tearing through the assumptions that have quietly underpinned the climate agenda.

Crimea in 2014 should have been a strategic shock. It wasn’t. Trump’s first term called out Europe on defence and energy security — and was arrogantly laughed off. Macron declared NATO “brain dead” in 2019. Even after the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, too many in SW1 clung to illusions.

These aren’t just cracks in the system — they’re evidence that the old framework has fundamentally collapsed. You touch on this in your piece, but I’d go further. The assumptions that have shaped the climate agenda since Rio — global cooperation, Western leadership, rules-based progress — no longer hold in a multipolar, fragmented, and competitive world. It’s not just that parts of the climate movement failed to account for geopolitics. It may be that the two are fundamentally incompatible. We need to stop pretending otherwise.

And it’s not just climate action that sits uncomfortably with this dark new era. Many of the post-Cold War liberal projects — from global trade rules to human rights regimes — were premised on a unipolar, cooperative world that no longer exists.

There’s a parallel here that’s hard to ignore: climate multilateralism has become to Western liberal progressives what Iraq and Afghanistan were to the neo-cons (full disclosure: I supported both) — a grand, idealistic project built on shaky assumptions about the world, sustained by institutional momentum, and now colliding with history.